The Development of Cyber Law: Past and Future

Cyber law is often seen as a developing field in terms of international law. And rightly so, considering that the internet is a relatively new development in human history. However, that’s not to say that there isn’t development within the field of cyber law. The field encompasses a broad range of topics such as Intellectual property, data privacy, censorship etc, and some laws regarding cyber law are clearly defined. But despite that, this paper will narrow the scope in terms of where cyber law is the least developed, arguably that is within the context of data privacy and unauthorized access. These laws are often the least developed because they used to be enforced by legislation that covered traditional communication networks, such as mail and phone networks. But since data and unauthorized access is the least developed that means they are often the most abused by agents committing cybercrimes. Feasibly, this is mainly due to the fact that these sectors lack enforcement and detection methods. However, in regions where cyber law is most enforceable have decided to back enforcement and detection mechanisms that allow their cyber law to be practically enforced. But in order to understand how that’s possible a bit of background information on cybercrime and cyber law is necessary.

Background

Cybercrime has existed since the 1970’s in the form of network attacks on phone companies. Hackers would infiltrate telephone networks enabling them to create connection, reroute calls, and use payphones for free (The History of Phone Phreaking). This early era of hacking was a problem due to the lack of legislation that could act as a guide for law enforcement to accurately charge criminals. Arguably, it was the lack of legislation on hacking which allowed computer hackers to hone their techniques of network infiltration and data theft. The reason why that’s so can be observed in the late 1980s, where the intensity of large system attacks became more abundant and destructive. One of these major system hacks was perpetuated by a group known as 414. It may come as a surprise that this group wasn’t a group of hardened criminals, but rather 6 teenagers from Milwaukee, Wisconsin. These teenagers managed to hack high profile systems ranging from a nuclear power to banks (Stor). The intentions of the hackers didn’t seem maligned, since they didn’t steal any info from these systems. But the 414 hacks weren’t harmless either since they cost a research company $1,500 after the hackers deleted some billing records. But other major hacks weren’t as harmless. The notorious Morris worm is a prime example of the harmful effects of unwarranted network infiltration. The reason that’s the case is that it the Morris Worm was one of the first hacks that was distributed to the public internet (Sack). The worm was created by Robert Morris a Graduate student at Cornell in order to showcase the security problems of the internet, the worm would go on to cause in-between $100,000- $10,000,000 in damage by infiltrating networks and causing them to become non-operational (Newman). Clifford Stoll, one of the people responsible for purging the worm, described the Morris worm as such:

“I surveyed the network, and found that two thousand computers were infected within fifteen hours. These machines were dead in the water—useless until disinfected. And removing the virus often took two days.” (Sack)

Additionally, one of Stoll’s colleagues says that 6,000 computers were infected, which may not seem like much but only 60,000 computers were connected to the internet at that time. Meaning 10% of the internet was infected (Sack). Such attacks would force legislators to address the problems of cybercrime, specifically network infiltration. One of the first pieces of comprehensive cyber law to address these issues was the Computer Fraud and Abuse Act enacted by the United States congress.

Computer Fraud and Abuse Act

After a lieu of cyber-attacks plagued the world, the U.S Congress decided to specifically address cybercrime. Prior to the Computer Fraud and Abuse Act (CFAA) cybercrime was prosecuted under mail and fraud, however that proved uncomprehensive. The CFAA’s framework defined what cybercrime entailed. One of the pioneering things the legislation did was define what kinds of computers were off limits to data infiltration. According United States code, In Title 18, Section 1030 of CFAA a computer is unlawful to hack if that computer is:

“(A) exclusively for the use of a financial institution or the United States Government, or, in the case of a computer not exclusively for such use, used by or for a financial institution or the United States Government and the conduct constituting the offense affects that use by or for the financial institution or the Government; or

(B) which is used in interstate or foreign commerce or communication, including a computer located outside the United States that is used in a manner that affects interstate or foreign commerce or communication of the United States.” -18 U.S. Code § 1030 – Fraud and related activity in connection with computers (Cornell)

Basically, stealing information from a computer that effects the United States via interstate or foreign commerce/communication is forbidden. These specifications were enough to convict various individuals who committed cybercrimes in the late 1980s. Interestingly enough, Robert Morris was the first person to be convicted for violating the Computer Fraud and Abuse Act. Specifically, because he intended to infiltrate several computers without authorization which negatively affected economics and communication within the US (Newman). Arguably, the enforcement power of the CPAA may have been the essential precedent needed for the international community in terms of creating sufficient cyber laws.

Budapest Convention on Cybercrime

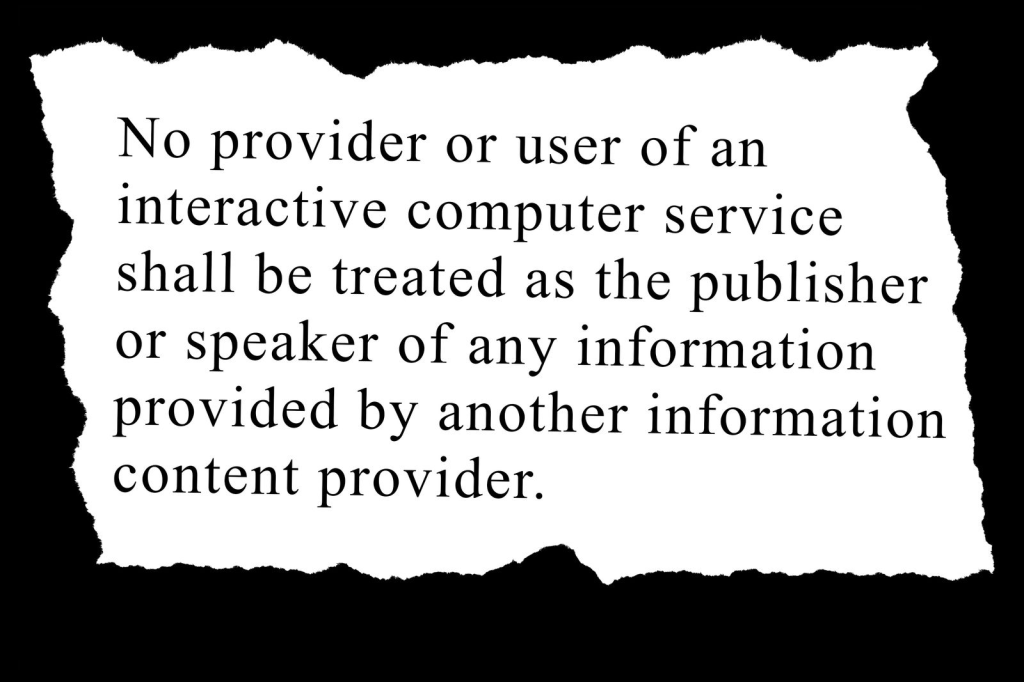

In November 2001, the first international convention on cybercrime took place. The scope of the Budapest Convention on Cyber Crime (BCC), unlike the CPA, had a wide range because it addressed: IP law, fraud, and child pornography. However, the convention also found it important to address what unlawful access to a computer constituted, defining it as:

“..A Party may require that the offence be committed by infringing security measures, with the intent of obtaining computer data or other dishonest intent, or in relation to a computer system that is connected to another computer system.” -Article 2 of BCC (Council Of Europe)

Here, arguably, the BCC is more specific then the CPAA in terms of defining unlawful access. The reason being is that it ignores the economic/ social effects and directly addresses what unlawful access is which would be:

“..the intent of obtaining computer data or other dishonest intent…to a computer system that is connected to another computer system”.

The BCC ignores the economic/ social effects because some hacks may not influence the economy or society, by keeping the CPAA definition, the scope of data infiltration would’ve been limited to social and economic consequences on specific nations. Furthermore, the BCC’s unlawful access clause has been a topic of discussion for legal entities and private corporations.

Modern Developments

EU v Facebook

The precedent set by the BCC on data infiltration remains relevant in contemporary times. Especially when considering the role private corporations have in data security. This is evident when taking Facebook’s recent big data breach into consideration. In order to understand why Facebook could potentially be an important catalyst to cybercrime we need to understand Facebook’s role on the internet. Simply put, Facebook is a social media website which connects private users via a public platform, but despite it being a public platform users’ can share data privately. However, controversy emerged after users’ data was allegedly being misdirected and sold to third parties without user’s complete consent(Guzenko). This is a clear violation of the BCC’s definition of unlawful system infiltration. The reason that could be so is that since Facebook is in charge of maintaining data security for their users, that would mean Facebook selling data without user’s consent would constitute unlawful data infiltration according to article 2 of the BCC. Additionally, Facebook was hacked by a third party and millions of users’ data was exposed without user consent. After this particular hack the European Union decided to step in and reprimand Facebook via a 1 billion euro fine (Schnechner). The EU argues Facebook didn’t do enough to protect users’ data from infiltration, but such accusations do little for cyberlaw. The reason for that is that the EU could always argue that an entity “didn’t do enough” to protect user data, and supplement that reasoning with a fine. Rather, since cyberlaw is a relatively new field, legal entities ought to cooperate with influential players within the cyber world in order to create viable solutions to cybercrimes. The EU accusations assume that Facebook is the entity which allows 3rd parties to access user’s data, but actually it’s the users themselves who allow it. Restricting one’s data is an option if a user changes their privacy settings. Additionally, It’s unrealistic to expect Facebook to curtail the behavior of its one billion users, some users may be more susceptible to data hackers due to their ignorance on data security. The reasoning the EU expels on to Facebook would be similar to this: If an EU citizen were to steal property from another citizen then the EU itself would be held accountable for allowing that to occur, and thus deserves to be fined. This is so because Facebook is similar to the EU, in that it’s a microcosm of different sets of people behaving in ways they can’t totally predict. So instead of focusing on how specific internet services operate, focus should be shifted to network self-enforcement. A prime example of that shift of focus would be China’s comprehensive self-regulating internet network.

China’s Internet Network

Modern cybercrime has evolved in terms of the magnitude of attacks. However, in the 21st century cyber attacks, particularly on infrastructure, are not only possible but prevalent (Schmitt). An example of such an attack is explained by Tomas Ball, a contributor to the Computer Business Review

“in December 2015 a massive power outage hit the Ukraine, and it was found to be the result of a supervisory control and data acquisition (SCADA) cyber-attack. This instance left around 230,000 people in the West of the country without power for hours…chaos was sewn using spear phishing emails, a low tech approach to launch such an attack; this trend is relevant today, with phishing still being used against critical infrastructure.” (Ball).

That’s only one case, but hacks on critical infrastructure can range from manipulating data which changes the chemical composition of drugs being manufactured, or to infiltrating a dam and redirecting electricity (Schmitt). Countries have implemented measures to mitigate and respond to this risk on critical infrastructure. A notable response to this problem has been from the Chinese government. China has been able to mitigate the risk of data infiltration by regulating its domestic network via legislation and technology. This may seem like a normal approach, but China is unique in the sense that it’s network is reinforced by technology which actively implements its cyber legislation. It’s difficult to understand the full scope of how China is able to do this (since the government isn’t transparent on how the network fully operates) but there are things that are clearly observable in terms of how data transfer is controlled. Firstly, data transfer in China is purposefully slowed. This is important because it allows the Chinese network to detect potential disturbances before they fully manifest, so infiltration could be detected much easier (Chew). Secondly, as mentioned before, the system self regulates. The Chinese government implements its own filters by creating comprehensive state tech that enforces Chinese law. However, China also puts heavy pressure on Chinese firms to self-regulate content, meaning that a firm that deals within the cyber world must follow the cyber laws or face a shutdown of business or a hefty fine. This is similar to how the EU went about dealing with Facebook, the only key difference being that the EU lacks its own data enforcement technology (Chew). And lastly, China’s network will respond to infringements of their cyber law by quickly “poisoning” unlawful data connections. An example of this would be if a hacker wanted to infiltrate some data network the connection would immediately be detected as a “poisonous connection” and thereby the hacker would be cut off from that connection (Chew). Arguably this is what sets China’s cyber network apart from everyone else, the ability to actively regulate data under their legal framework. Though it’s worthy to note that China’s network indeed does well in terms of enforcing its cyber law by regulating data, but that doesn’t mean the network is exempt from criticism.

China’s cyber network is rather effective in terms of enforcing its cyber law, however it has been used to disenfranchise its own civilian population. Qiang Xiao an internet researcher at UC Berkeley describes China’s internet network as such

“…it has consistently and tirelessly worked to improve and expand its ability to control online speech and to silence voices that are considered too provocative or challenging to the status quo.”(Xiao). But such things, unfortunately, should be expected. After all it makes sense for illiberal governments to manifest illiberal computer networks. But such realities shouldn’t deter liberal government from trying to conceptualize and develop internet networks which enforce cyber law. This is a lot easier said than done because it’s easier to enforce authoritarian cyber law than more liberal law (Schmitt).”

Mainly, due to the fact that the amount of computing power needed to create a liberal network would be immense. In conjunction with it being so massive, economic factors come into play when determining how effective cyber law is enforced in a region, leaving poorer liberal nations behind. Despite that, developments in quantum computing can allow for massive amounts of data to be processed and it’s getting cheaper as it develops (IBM). Not only that but quantum computing opens up the door for the network to self-learn, enabling better self-enforcement (IBM). Such features may intrigue governments who want to enforce a Common Law internet network since it can self-learn off of old legal precedents. So in the future enforceable cyber for liberal governments is definitely a possibility, and perhaps a necessity if strong cyber law is to be properly enforced.

In conclusion, since there are problems with enforcement and efficiency of cyber law, internet networks which actively enforce cyber law using the internet network itself are necessary to achieve practical cyber data enforcement. Different legal jurisdictions would naturally have different laws concerning their respective internet networks, therefore various network legal structures would need to exist to facilitate their cyber laws. Developments in quantum computing may pave the way for networks to regulate themselves.

Works Cited

“18 U.S. Code § 1030 – Fraud and Related Activity in Connection with Computers.” LII / Legal Information Institute, Legal Information Institute, http://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/text/18/1030.

Ball, Tom. “Top 5 Critical Infrastructure Cyber Attacks.” Computer Business Review, Computer Business Review, 18 Jan. 2018, http://www.cbronline.com/cybersecurity/top-5-infrastructure-hacks/.

“Budapest Convention on Cybercrime.” Council of Europe, Council of Europe, http://www.coe.int/en/web/conventions/full-list/-/conventions/rms/0900001680081561.

Chew, Wei Chun. “How It Works: Great Firewall of China – Wei Chun Chew – Medium.” Medium.com, Medium, 1 May 2018, medium.com/@chewweichun/how-it-works-great-firewall-of-china-c0ef16454475.

Guzenko, Ivan. “The Third-Party Data Crisis: How the Facebook Data Breach Affects the Ad Tech.” MarTechSeries, 5 July 2018, martechseries.com/mts-insights/guest-authors/the-third-party-data-crisis-how-the-facebook-data-breach-affects-the-ad-tech/.

“The History Of Phone Phreaking.” The History of Phone Phreaking — FAQ, http://www.historyofphonephreaking.org/faq.php.

Newman, Jon O. “UNITED STATES of America, Appellee, v. Robert Tappan MORRIS, Defendant–Appellant.” Stanford Law, stanford.edu/~jmayer/law696/week1/Unites%20States%20v.%20Morris.pdf.

Sack, Harald. “The Story of the Morris Worm – First Malware Hits the Internet.” SciHi Blog, 3 Nov. 2018, scihi.org/internet-morris-worm/.

Schechner, Sam. “Facebook Faces Potential $1.63 Billion Fine in Europe Over Data Breach.” The Wall Street Journal, Dow Jones & Company, 30 Sept. 2018, http://www.wsj.com/articles/facebook-faces-potential-1-63-billion-fine-in-europe-over-data-breach-1538330906.

Schmitt , Michael N. “Cyberspace and International Law: The Penumbral Mist of Uncertainty.” Harvard Law Review, harvardlawreview.org/2013/04/cyberspace-and-international-law-the-penumbral-mist-of-uncertainty/.

Stor, Will. “The Kid Hackers Who Starred in a Real-Life WarGames.” The Telegraph, Telegraph Media Group, 16 Sept. 2015, http://www.telegraph.co.uk/film/the-414s/hackers-wargames-true-story/.

“What Is Quantum Computing?” What Is Quantum Computing? , IBM, http://www.research.ibm.com/ibm-q/learn/what-is-quantum-computing/.

Xiao, Qiang. “Recent Mechanisms of State Control over the Chinese Internet – Xiao Qiang.” China Digital Times CDT, chinadigitaltimes.net/2007/07/recent-mechanisms-of-state-control-over-the-chinese-internet-xiao-qiang/.