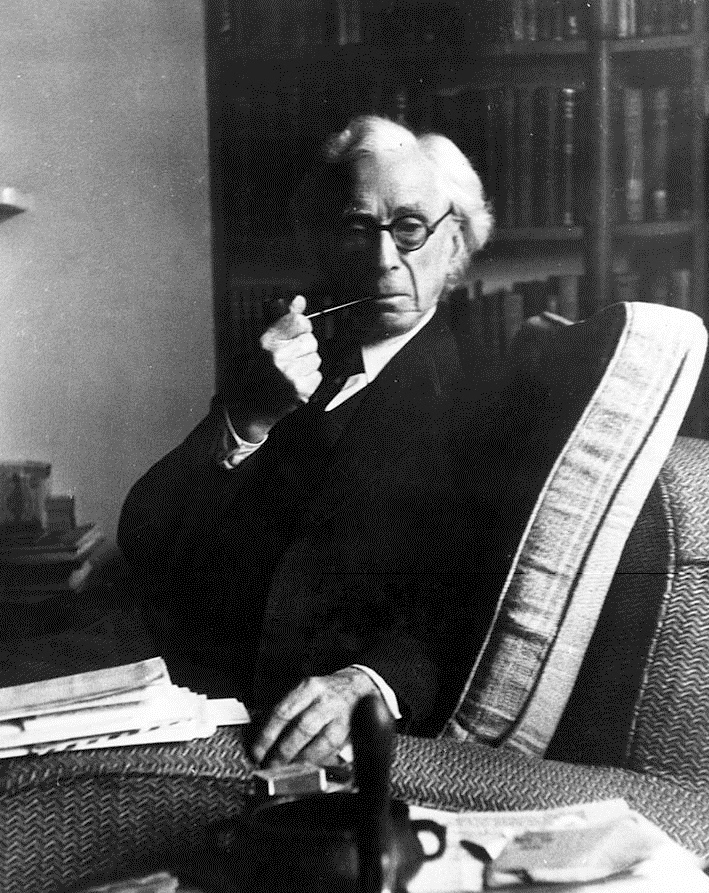

Often Bertrand Russell is revered in the mainstream philosophical community. And rightly so, the work he’s done in the fields of logic, linguistics, and mathematics have had a profound impact on the world. His influence has led him to be credited as the founder of analytic philosophy. But people often forget that Russell was also interested in history, so much so that he penned a lengthy history of Western Philosophy, which he called A History of Western Philosophy. This article will discuss Bertrand Russell’s account of Heraclitus and Thales. Two philosophers who came before Plato and Aristotle. The reason such a discussion is necessary is due to the fact that Russell may not be giving an accurate portrayal of either philosopher in his book. The reason being is that Russel relies on problematic sources to back his claims. This piece will attempt to outline the thoughts Russell had on these thinkers, and then we will criticize certain elements of his arguments. But in order to conduct a proper analysis we must understand the overal goal of Russel book.

In the History of Western Philosophy Bertrand Russell attempts to provide a coherent timeline for western philosophical thought. He claims that in order to successfully attempt such a project a specific method of analysis must be used. A method which is “philosophical”. By “philosophical” Russell means that he’ll attempt to synthesize the historical development of two different styles of inquiry, those being scientific and theological traditions (Russell Xiii). Both have different functions, but yet throughout history they’ve reinforced one another in various ways. For Russel, theology is useful because it allows us to make “speculation on matters as to which definite knowledge has, so far, been unascertainable.”(Russell Xiii). In other words, theology allows human reason to explore the unknowable. Now on the other hand, science allows human reason to explore the knowable (Russell Xiv). According to Russell, both have limitations; theology induces dogmatic belief (which he disapproves of), while science tells us what we can in fact know but “what we can know is little” (Russell xiv). Having acknowledged their flaws, Russell proceeds to argue that the development of human intellectual history has been shaped by those two methods of inquiry interacting with one another over time. Theology picks up the methodological flaw inherent in science, and vice versa. It’s this symmetric relationship which allows Russell to put various thinkers in dialogue with one another. Giving readers a coherent narrative to follow in terms of the development of western philosophical thought. But Russell’s methods have drawn scrutiny amongst critics. Frederick Copleston, a contemporary of Russel, acknowledged that “[Russell] treatment of a number of important philosophers is both inadequate and misleading.”. The inadequacy and misleading nature of Russell’s work is evident in his description of two philosophers who came before Socrates, Thales and Heraclitus.

Bertrand’s Thales

In order to understand and identify the “inadequate and misleading” elements of Russel’s work we must analyze his descriptions of certain philosophers. Some of the problematic elements of his descriptions can be found when he describes Thales, a thinker who was active in the 6th century BCE. To be frank, little is known about Thales specific work, as none of his writing survived. But despite that fact, society can get a general idea about Thales by reading some second hand accounts about his teachings. Russell provides an introduction to Thales, writing:

“There is…ample reason to feel respect for Thales, though perhaps rather as a man of science than as a philosopher in the modern sense of the word.” (Russell 24)

This sentence should warrant our attention because we can analyze and infer a few things from Russell’s statement. One, that Bertrand holds Thales in high regard compared to the other philosopher of that particular era. And secondly, we should hold a favorable opinion on him because compared to these philosophers Thales is a “man of science”. Why does Russell feel this way? Well, it all stems from a theory attributed to Thales which professes that everything is made of water. A problematic theory to credit onto Thales in the first place, but the reason for that will be addressed in a different section in this paper. Russell explains that Thales’s theory of water shouldn’t be taken as some “foolish” hypothesis but rather as a scientific hypothesis (Russell 26).

Now the reason he feels like Thales warrants such high praise is due to some scientific discoveries made while he wrote his book. While Russell was writing his book in the 20th century, the scientific consensus seemed to match well with Thales water theory. The consensus was largely contingent on the fact that the theoretical work done by the scientist Willaim Prout on atoms was true. Prout hypothesized that the hydrogen atom was the only fundamental element of the universe. Furthermore, he said that the atoms of other elements were actually just collection of different hydrogen atoms (Rosenfeld). This is similar to Thales’s theory since hydrogen is a pretty important component when it comes to water, but is different since Prout specifies the element hydrogen. So this background information helps explain why Russell felt so confident in Thales. And explains assertions such as this:

“ The statement that everything is made of water is to be regarded as a scientific hypothesis… Twenty years ago, the received view was that everything is made of hydrogen, which is two thirds water…. His [Thales] science and his philosophy were both crude, but they were such as to stimulate both thought and observation.” (Russell 26)

Now the last part of that sentence describes how his science and philosophy were “crude” but are acceptable since they aimed to stimulate both thought and observation. So, one can infer that theoretical frameworks which stimulate thought and observation, are ones which Russell approves of. But Russell also lets readers know what kind of frameworks he doesn’t appreciate. That leads us to Russell’s description of Heraclitus.

Bertrand’s Heraclitus

The way Heraclitus is portrayed in Russell’s book plays on the theme of science and theology interacting with each other overtime. Russell generally views Heraclitus in a negative light, but acknowledges the difficulty science has had in refuting Heraclitus’s theory of perpetual flux. Additionally, Heraclitus is strangely categorized as “mystical” rather than “scientific”. Russell describes the nature of Heraclitus thought as such:

“Heraclitus, though an Ionian, was not in the scientific tradition of the Milesians. He was a mystic, but of a peculiar kind. He regarded fire as the fundamental substance, everything… is born by the death of something else “ (Russell 41)

Russell doesn’t give us a clear reason why Heraclitus shouldn’t be considered scientific, but we can imply that it’s due to his heavy reliance on intuition and speculation. Heraclitus brand of mysticism is categorized as reforming the religion of his day (Russell 42). Additionally, elements of Heraclitus doctrine are criticized by Russell. Specifically he attacks Heraclitus views on war, contempt for mankind, and his disapproval of democracy.

Now having outlined what Russell says about these thinkers. It’s time to shift focus on what Russell may have gotten wrong when discussing these philosophers. For instance we can use the reasoning Bertrand used to praise Thales to talk about Heraclitus as a “scientific thinker”. Additionally, we can also conceive as Thales as a “mystic”. Furthermore, we can learn to understand how Russell came to these conceptions when investigating the sources he decided to use.

Analysis of Russell’s claims

Our criticism of Russell should begin with looking at what kind of information Russell based his critiques on. He’s pretty transparent in letting the readers know where he got his information from, writing:

“According to Aristotle, he thought that water is the original substance out of which all others are formed; and he maintained that the earth rests on water”(Russell 26)

But there’s an issue with Russell’s apparent transparency. In the next paragraph he goes on to take Aristotle’s account as pure fact, and basis his entire scientific description of Thales on it. Never once does the problematic nature of Aristotle’s account of Thales get mentioned. But thankfully, recent scholarship done by Frede tells us why Aristotle’s writings on Thales aren’t to be taken as absolute fact. Frede explains that:

“ it is not Aristotle’s aim to provide an account of his origin of philosophy and its evolution for its own sake, to satisfy his and his readers own historical interests “(Frede 503)

Basically, Frede notes that Aristotle wasn’t entirely fair when it came down to providing accurate descriptions of certain thinkers, but rather was using their doctrines to validate his work (Frede). Now having considered that fact Thales can be seen as a mystic because not a lot of his doctrine was written down, and getting an accurate description of his work is difficult. But the school of thought he was a part of (the Milesian school) had mystical tendencies that Bertrand speaks of. Additionally, Aryeh Finkelberg notes that:

“Heraclitus, and other early Greek thinkers, did not set out to found philosophy and science, or pave the way for Aristotle—who has long been criticized “for reading his philosophical concerns into the early thinkers (Finkelberg, Heraclitus and Thales’ Conceptual Scheme). “So the method Bertrand uses to put them in dialogue together is problematic since none of these thinkers thought of themselves as either scientists, philosophers or mystics.

Now having mentioned the problematic nature of the sources, I will provide sources which allow us to think of Thales as a “mystic” and Heraclitus as a “scientist”. To begin I will refer to a source used by Russell himself- Aristotle. As noted previously Russell relies on Aristotle’s account of Thales to prove that the thinker was indeed scientific. But he conveniently leaves out an account that could hint at him being less “scientific”. In Aristotle’s work On the Soul Thales is framed as a thinker who’s influenced by “mysticism” and attempts to explain the world via religious terms. The account goes as such:

“Thales too (as far as we can judge from people’s memoirs) apparently took the soul to be a principle of movement…Some say that the universe is shot through with soul, which is perhaps why Thales too though that all things were full of Gods”( Aristotle, On the Soul 405a)

There’s a lot to unpack from this phrase. Firstly, Aristotle is relying on testimonials from various people to get Thales’s account on souls. So we can infer that Thales Soul/Movement Theory was one that was known and discussed among contemporaries that were familiar with Thales. Secondly, we can see that Thales theory is based on metaphysical concepts (soul), and that these concepts have at least some effect on our material world (movement). And lastly, we can surmise that Thales’s world view largely consists of things having Gods within them. Arguably, this is a pretty “mystical” way to perceive reality. But from this phrase it’s unclear if Gods and Soul are in the same realm in terms of metaphysics. From the quote, soul is something metaphysical since it’s “principal of movement” and not movement itself. But Gods can be seen as both physical and metaphysical, since the universe being “shot with Soul” would have impact if whether things were filled with Gods or not. But it’s unclear from this reading if Gods are physical, metaphysical, or both. What we can clearly analyze is that Thales does have some mystical element in his analysis. Rendering Russell’s description as inadequate and a bit misleading.

Furthermore, Thales theory of water as the fundamental source of everything isn’t necessarily true. He may have never postulated that. Aristotle explains that he did indeed say that water is the fundamental source, but he also claims that he may not have seen it that way after all. Explaining that the earth and water could be reinforcing each other as elements ( Aristotle,On the Heavens, 292-294b). Thales could’ve easily believed that there didn’t need to be one principal element that’s responsible for everything. For all we know Thales could’ve theorized that several elements contributed to the forces of the world. But because Aristotle is using Thales to justify his own theories, conceptualizing him as a philosopher who believes that one fundamental source is responsible for everything is necessary in order to legitimize Aristotle’s views .

Let’s transition over to Heraclitus, aka the “mystical” thinker. Firstly, I’d like to mention that Russell dismissal of the claim that “everything is fire” and approval of “everything is water” is absurd. The way he justifies his reasoning, though understandable, is equally as silly. He uses Prout’s work on atoms to back up that claim but you could do the same for Heraclitus. After all everything in the universe emits heat, and if we understand fire to mean “element that emits heat”, then (considering 21st century physics) Heraclitus theory shouldn’t be taken as foolish either. Further, he can been seen as scientific due to observations such as these:

“Sea: water most pure and most tainted, drinkable and wholesome for fish, but undrinkable and poisonous for people”( Hippolytus, Refutation of All Heresies,)

&

“Corpses should be disposed of more readily than dung” (Strabo, Geography).

The first quote is an empirical observation on how one element can nourish one animal but yet be dangerous to another. While the second can be interpreted as a public service announcement that corpses are as unsanitary as dung. Though not completely “scientific” in our modern use of the term, these statements are observations on the general nature of the world, and are valid. Thales allegedly made similar observations but Russell holds him in higher esteem compared to Heraclitus.

In all we can see that Bertrand Russell’s claims in the History of Western Philosophy are problematic. Mainly because the notion that these thinkers were either scientific or mystical are inaccurate conceptions in the first place,since the thinkers didn’t even see themselves as such. And since we can conceptualize each thinker as both a “mystic” and “scientist” Russel’s analysis is misleading. Furthermore, the evidence used by Russell isn’t the best since the source itself, Aristotle, is biased.

Source(s):

Frede, Michael. “Aristotle’s Account of the Origins of Philosophy – Oxford Handbooks.” Oxford Handbooks – Scholarly Research Reviews, 27 Apr. 2018, http://www.oxfordhandbooks.com/view/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780195146875.001.0001/oxfordhb-9780195146875-e-20.

“Heraclitus and Thales’ Conceptual Scheme.” Heraclitus and Thales’ Conceptual Scheme | Reading Religion, 31 May 2017, readingreligion.org/books/heraclitus-and-thales-conceptual-scheme.

Rosenfeld, Louis. “William Prout: Early 19th Century Physician-Chemist.” Clinical Chemistry, Clinical Chemistry, 1 Apr. 2003, clinchem.aaccjnls.org/content/49/4/699.

Russell, Bertrand. History of Western Philosophy. Routledge, 2015.

Aristotle: On the Soul and On the Heavens

Hippolytus: Refutation of All Heresies,

Strabo: Geography