The Origin of Feed-In Tariffs

Going into the 21st century Germany has rapidly developed its renewable energy sector. A large reason for that growth are feed-in tariff policies. In contrast, the United States has not developed their renewable energy sector at the same rate or fashion as their European counter parts. This blog will aim to investigate why the US hasn’t developed their renewable energy policies, a large part owing to the relative lackluster feed in tariff programs.

In general feed-in tariffs (FiTs) are performance-based incentive (1) supporting renewable energy generation (2) guaranteeing payments to a producer for total kWh produced, (3) access to the grid and (4) a long-term contract, and/or similar additional terms. The origins of FiT programs can be found investigating the U.S. and Germany.

The US Energy Crisis & PURPA

The U.S. is where the first form FiT programs were implemented. During the late 1970’s, the US was facing an energy crisis stemming from various factors, both domestic and international . The Carter administration and Congress were tasked with implementing policies which mitigated the economic effects stemming from the energy crisis. The U.S. desperately needed to diversify its energy portfolio to mitigate both real and potential economic losses. The National Energy Act (NEA) was subsequently passed as legislation in response to the growing issue. The stated purpose of the NEA was to encourage energy conservation and efficiency. It also aimed to develop new energy resources which included renewable sources such as wind and solar power. The NEA contained five acts, one of which was called the Public Utility Regulatory Policies Act (PURPA) which was where the first form of FiT programs began to develop.

PURPA requires electric utilities to make purchases of electric energy from co-generation facilities and small power production facilities that are at 80 MW or less in size at a rate that does not exceed the incremental cost to the electric utility of alternative electric energy ( see Public Power, 2020, p. 1-2) This requirement is commonly referred to as the avoided cost. Due to federalist principals underpinning American jurisprudence, the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC) and the individual states are the ones that are responsible for implementing PURPA. FERC primarily determines what constitutes a qualifying facility and provides guidance on avoided costs. Avoided costs are meant to mirror the cost a utility would incur to facilitate that same electrical generation (see Public Power, 2020, p. 2-3)

As disputes filtered through the US legal system various interpretations of PURPA began to take shape. Some of the utilities and state utility commissions construed avoided costs narrowly. They believed avoided cost only included avoided fuel costs. Other utilities and state commissions chose a broader interpretation for “avoided costs” as the “avoided long-run marginal cost” of generation. Another provision included PURPA was that utilities were prevented from owning more than 50% of projects, to encourage new market entrants. Over time states began to offer contracts (known as Standard offer Contracts) to producers. These contracts used fixed prices based on the expected long-run cost of generation. (Graves, Hanser,& Basheda 2- 13). The long-run estimates of electricity costs were based on the widely held assumption that gas and oil prices would continue to increase .Id. This led to an escalating schedule of fixed purchase prices, designed to reflect the long-run avoided costs of new electrical generation. (Louise Guey-Lee, 1999, p 92-96). The adoption and implementation of PURPA lead to ample amount of renewable energy generation in certain states. Furthermore, by the mid 1990’s power producers installed roughly 1,800 MW of wind Capacity in California. Some of those systems are still being used and serviced to this day. The Standard Offer contracts can be called the first form of FiTs since producers were compensated for (1) KwH produced, (2) given access to the grid, (3) incentivized the development of renewable energy sources and (4) the contracts were long term.

Overtime, gas and oil prices went down and the energy crisis subsided. This made the PURPA Standard Offer contracts that encouraged renewable development a lot less attractive since oil and gas could now be purchased a lot cheaper. That meant there was little incentive to generate renewable energy sources because the oil and gas market recovered back to their favorable prices. Further, large utilities felt threatened when it came to their market share. That is because PURPA was partly implemented to encourage non-utility generation, which could threaten a monopolistic utility’s market share. Further, some industrial suppliers began to build inefficient generators which though met PURPA’s regulatory requirements, lead to market and ecological inefficiencies. These factors likely contributed to the steady decline of these kind of PURPA contracts that encouraged renewable generation. Though the US’s first form of a FiT program was declining into the 20th century, in another part of the world the most robust feed in tariff policy began to sow its seeds.

Stromeinspeisungsgesetz: Germany’s Feed-in Tariff

Germany is where the first comprehensive FiT program developed. In the early 1990s, a piece of energy legislation spearheaded by Matthias Engelsberger would pass through the German Bundestag to become federal law. That piece of legislation was called the Stromeinspeisegesetz (“StrEG”) (translated from German ‘electricity feed-in law’). This is the first piece of legislation that explicitly calls itself a feed-in tariff law.

StrEG was the first time the world would be introduced to a systemic feed-in tariff program that would operate in the free market. The program mandated that network operators purchase electricity produced by renewables, as long as a large utility did not produce the energy. (Allen & Davies,2014, pg 937-938). And it established incentive prices that had to be paid for those purchases (Id). These innovations were key to StrEG’s success. That’s because the mandatory purchase requirement eased the process for German renewable generators to bring their product to market. For example the law stipulated that:

“Generators were not required to negotiate contracts or otherwise engage in much bureaucratic activity”.(Lauber & Mez,, 2004, pg. 3)

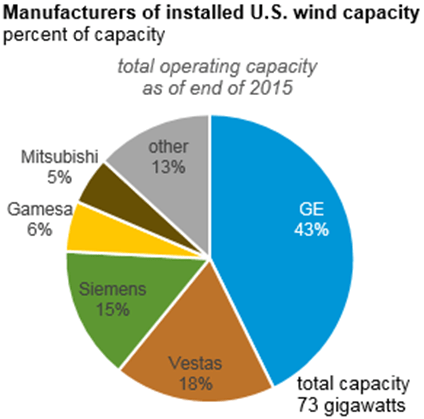

This meant that StrEG removed an important barrier to entry because it was StrEG that imposed the mandate to connect and purchase electricity. This stipulation meant that the process for energy generators was significantly simplified. Had that stipulation not existed monopolistic utilities would have likely resisted efforts by new entrants to connect with their networks. (Allen & Davies,2014, pg 937-938). The graph below shows the market share of wind turbine manufactures in Germany during 1998(top) and US market share in 2015 (bottom). Germany had about the same amount of manufactures the US has now:

Going into the 21st century, the German Bundestag decided to restructure the policies found in the StrEG. In the 2000s they reinforced their FiT policy by passing the ‘Eneuerbare-Energien-Gesetz (EEG) which in English translates to ‘Renewable Energy Sources Act’. The EEG added three new initiatives to StrEGs. First, the EEG adopted the Aachen model and decoupled feed-in rates from retail electric prices. (Gipe 2007). The Aachen Model takes its name from a city in Western Germany. That city implemented one of the best policies during the StrEG era, instead of paying renewables producers a percentage of retail rates, Aachen established a solar FiT based on the technology’s cost, plus an adder to cover a modest investor profit. (Gipe, 2007). German policy makers saw this as an innovate measure because previous support mechanism tended not to reflect the price of the technology itself but rather external factors such as retail electric prices or conventional generation prices (Allen & Davies, 2014, pg 943). Second, the EEG had fixed periods of time that the feed-in rates would be paid which was usually twenty years (Id). This was a major change since previously under the StrEG, the duration of tariff payments was not specified. Finally, the EEG created a stronger investment incentive for renewables by prioritizing electricity produced from these resources over others. (Id). Therefore, German FiT had these four fundamental characteristics (1) the mandatory purchase of renewable electricity by grid operators, (2) at cost-based tariff rates guaranteed for twenty years, (3) with a priority for renewables use on the system, and (4) mandatory grid connection.

EEG was able to rapidly develop Germany’s renewable energy sector. That’s because it made renewable energy production simpler in Germany. For example, in America a typical power purchase agreement between a producer and utility would be 85 pages. While in Germany the average contract is 2-4 pages. (Farrell, 2014, pg. 14). They also make the market fairer by removing barriers of entry, entities with little to no tax liability can participate. And finally, since FiT contracts are long term they offered more stability and predictability.

Despite the EEG’s efficacy over time in developing the renewable sector, there is still plenty to critique.

The Negatives

EEG has had a beneficial impact on Germany’s renewable sector, but it has come at significant monetary cost for tax payers. In total estimated cost over these past 20 years hover around $200 billion. (Reed 2017). There are roughly 80 million Germans living during that time which means each paid about $2,500 dollars in taxes to fund these programs. Furthermore, consumers in Germany pay some of the highest rates for electricity in comparison to consumers in the US and UK. (Id).

Christop Podewils, an energy policy analyst highlights an interesting problem with EEG “It’s about saving money, but there aren’t many opportunities to save money…you can’t shave the old contracts, and new contracts are very cheap.”. Over time renewable tech has gotten better which means some electric producers are fixed at rates that do not reflect the price to produce the electricity in contemporary time. For example, a homeowner with a rooftop solar system who signed an EEG contract in 2009 is compensated 43 cents per kilowatt-hour through 2029. Now the rate for a similar system would pay no more than 13.7 cent, less than half of the 43 cent rate. Lowering new tariff prices will not affect the backlog of previous high price contracts. Lawmakers in Germany have been trying to find measures to counteract this affect, but most of the solutions run counter to principals of German contract law. (Farrell, 2014, pg. 14). The only apparent option is the passing of a new EEG bill that cuts some of the unnecessary expenditure the inefficient contracts create.

A reform bill has been proposed which would cut exemptions for industrial customers, impose a surcharge on customers who generate their own power, put caps on new developments, further accelerate the decline in payments for certain renewables, and cutting “market incentives” to sell renewables on the power exchange. (Paulos 2014). Exemptions are given to 2,100 companies that are “electricity-cost intensive and trade intensive,” according to the Ministry of Economic Affairs and Energy (BMWi). Generally these companies use 25 percent of Germany’s power, but only pay 2 percent of the surcharge. (Paulos 2014). Residential and small commercial customers pick up the cost, paying roughly 30 billion dollars a year. High energy costs are harmful for consumers. Especially indigent consumers since they will likely have to pay higher proportion of their income to meet their energy needs. The European Bank has studied this issue extensively and has noted that Germany’s EEG could exacerbate economic conditions for certain segments of their society. (Fankhauser & Tepic 2005). That is because renewable development has been focused away from poorer communities, meaning these community members may find it harder for them to heat and power their homes in an efficient manner. These consumers help finance the renewable grid, but do not get to directly benefit from the service. This can lead to resentment to the energy policy since the consumer pays but does not benefit from the service.

In essence the EEG has greatly expanded renewable development by mandating 1) the mandatory purchase of renewable electricity by grid operators, (2) at cost-based tariff rates guaranteed for twenty years, (3) with a priority for renewables use on the system, and (4) mandatory grid connection. Along with several amendment that expanded EEG. However, these measures have come at a great monetary cost for the German Government and German taxpayer.

Though the US is where the first form of FiT developed, those polices would not thrive in the 21st century. Unlike Germany, the U.S. has not implemented any federal feed-in tariff legislation. There has however been significant legislative activity within the states.

The California Model

The German Bundestag had Aachen as a model for their FiT policy design and implementation. But if the US were to enact a federal FiT program they would likely use California as a referential model. Mainly because California has one of the most robust and successful FiT programs in the US. There are plenty of factors that explain that. As noted before FiTs can be expensive to implement. Government expenditure can easily rise over time. California is an international economic powerhouse, and so their government has the capital to create a lucrative FiT program. Furthermore, California is also one of the “tech hubs” of the world which makes a favorable economic environment for developing new renewable tech. They are also leaders in renewable technology. These market conditions make California prime for FiT programs.

In 2008 The California Public Utilities Commission (CPUC) approved an FiT. The CPUC press paper stated that :

The power that is sold to the utilities under the feed-in tariffs will count toward the utilities’ Renewables Portfolio Standard (RPS) goals. California’s RPS program is one of the most ambitious renewable energy standards in the country. The RPS program requires electric corporations to increase procurement from eligible renewable energy resources by at least 1 percent of their retail sales annually, until they reach 20 percent by 2010.

This marked California’s first FiT program. Shortly thereafter, Marin Energy Authority launched the first Community Choice Aggregate Feed-in Tariff program. The program was updated in November 2012, and now offers 20-year fixed-price contracts, with prices varying by energy source (peak, base-load, intermittent) and progress towards the current program cap of 10-MW. (MCE Clean Energy). California would then enact state laws which would greatly expand it’s FiT program. Some of these laws allowed homeowners to sell excess power that they generated to utilities. One of these laws was the California Solar Initiative (CSI). Unlike the German EEF, The CSI stipulated that customers were not allowed to install systems that overproduced, encouraging efficiency. (Id).

According to a study conducted by Dan Kammen and Max Wei at Berkeley’s Renewable and Appropriate Energy Laboratory Energy and Resources Group, a well-designed FiT could bring California $2 billion in additional tax revenue and $50 billion in new investment, while adding an average of 50,000 new jobs a year for a decade. (Kammen and Wei). But such progress may be diminished. Recently a FiT program called Re-MAT was deemed to be unconstitutional by the federal courts. (See Winding Creek Solar LLC v. Michael Peevey, et al.). A company failed to secure a Re-MAT at what they deemed an acceptable price, so they decided to challenge the constitutionality of the program in federal court. The Northern District of California held that the Re-MAT program conflicts with PURPA and its implementing regulations and thereby violates the Supremacy Clause of the U.S. Constitution. The court made two factual determinations: One was that the CPUC’s imposition of caps in the Re-MAT program violates PURPA’s must-take obligation for QFs, and secondly that the procedure for setting Re-MAT pricing strays too far from the PURPA requirement that QF contract pricing be set on a utility’s but-for cost. These types of court decisions signal that the FiT market in California is not predictable and therefore not the most stable.

Lessons for the US

The most obvious measure the U.S. would likely benefit from is a federal FiT program. Ideally the federal legislation would offer a significant latitude of power to the states in implementing their state FiT programs. The US is different both culturally, geographically, and economically than Germany, so an EEG replica would not necessarily work everywhere. Some states like California could copy and paste the EEG into their state law and see significant benefits. (Stokes 2013). But some states like Wyoming would have to operate differently. If there was federal legislation it would have to be catered away from the “one size fits all” theories of legislation. FiTs need to be allowed to be flexible to develop a state’s renewable energy sector.

Another key factor would market participation from all consumers and producers. FiT’s in the US should be inclusive of both large utilities, startups, and average consumers. This could encourage market participation since everyone has an “equal” chance to participate in FiTs with little to no barriers. (Stokes 2013). But as seen in the amendments made overtime in the German EEG, any exemptions to the rules made for certain entities should be continuously evaluated to make sure participants do not financially abuse the FiT system.

Special Thanks To the Sources below

Burger, Bruno. “ Public Net Electricity Generation in Germany 2019.” https://doi.org/https://www.ise.fraunhofer.de/en/press-media/news/2019/Public-net-electricity-generation-in-germany-2019.html.

Farrell, John. “Feed-in Tariffs in America Driving the Economy with Renewable Energy Policy That Works .” New Rules Project, https://doi.org/https://ilsr.org/wp-content/uploads/files/feed-in%20tariffs%20in%20america.pdf.

“Feed-in Tariff: Solar, Wind, Biomass.” MCE Community Choice Energy, 1 Dec. 2021, https://www.mcecleanenergy.org/feed-in-tariff/.

Frank Graves, Philip Hanser, Greg Basheda. “PURPA: Making the Sequel Better than the Original .” Edison Electric Institute, Dec. 2006, https://doi.org/https://puc.sd.gov/commission/dockets/electric/2011/EL11-006/puctestimony/roundsexhibit1.pdf.

Gipe, Paul. “All About Solar Energy: The Aachen Solar Tariff Model, Wind-Works.” 7 Apr. 2007, https://doi.org/http://www.wind-works.org/cms/index.php?id=38&tx_ ttnews%5Btt_news%5D=227& cHash=e088827563342ea235137c8e2e5f7cf6.

Gründinger, Wolfgang. “What Drives the Energiewende?: New German Politics and the Influence of Interest Groups .” https://doi.org/https://www.wolfgang-gruendinger.de/wp-content/uploads/2015/06/6-renewables-.pdf.

Guey-Lee, Louise. Renewable Electricity Purchases: History and Recent. 1999, http://www.keei.re.kr/keei/download/ef0505_60.pdf.

Lincoln L. Davies, and Kirsten Allen. “Feed-In Tariffs: In Turmoil .” West Virginia Law Review, vol. 116, 2014.

Paulos, Bentham. “Are the Legacy Costs of Germany’s Solar Feed-in Tariff Fixable?” Greentech Media, Greentech Media, 3 June 2014, https://www.greentechmedia.com/amp/article/germany-moves-to-reform-its-renewable-energy-law.

“The Public Utility Regulatory Policies Act of 1978.” Public Power, https://www.publicpower.org/system/files/documents/2021-Public-power-Statistical-Report.pdf.

Rabe, Madita. “Why Did OPEC Lose Its Price Setting Power During the 1980s?” New Research in Global Political Economy, https://doi.org/https://kobra.uni-kassel.de/bitstream/handle/123456789/13009/New_Research_in_GPE_2_2021.pdf?sequence=3&isAllowed=y.

Reed, Stanley. “Power Prices Go Negative in Germany, a Positive for Energy Users.” The New York Times, The New York Times, 25 Dec. 2017, https://www.nytimes.com/2017/12/25/business/energy-environment/germany-electricity-negative-prices.html.

Stokes, Leah C. “The Benefits and Challenges of Using Feed-in Tariff Policies to Encourage Renewable Energy.” Scholars Strategy Network, https://scholars.org/contribution/benefits-and-challenges-using-feed-tariff-policies-encourage-renewable-energy.