As the world approaches another economic recession due to COVID-19, the Frugal Five (Austria, Denmark, Germany, the Netherlands, and Sweden) have decided that southern Europe is at fault for not preparing enough for the crisis. After an emergency meeting conducted by the European Union, the Frugal Four voiced their discontent for having to be punished for saving for a rainy day. This outcry has reopened an old “beef” between northern and southern European nations. Remember that in the early stages of the eurozone crisis in 2008 the Frugal Four were among the most vocal opponents of the initial Greek “bailout”. They demanded drastic austerity measures in return for emergency bailouts. The former Dutch finance minister Jeroen Dijsselbloem gained widespread notoriety for his pocket watching while negotiating the Greek debt response. Let’s remember at one time he suggested that his southern European neighbors had wasted their money on “booze and women”. He wasn’t the only high level representative to hold such views. Angela Merkel complained that southern Europeans retire too early and don’t work as hard as their northern counter parts. The Frugal Four have continuously obstructed sound responses to economic crisis for the sake of upholding an economic ideology called ordoliberalism. But times like this call for action detached from fervent idealism.

The work below will show you how ordoliberalism has negatively influenced the EU’s response to economic catastrophes. Germany will be scrutinized since it is the most influential in terms of monetary policy in the EU.

Germany’s Economic Miracle

Ever since Germany’s ’economic miracle’ that followed World War II, there’s been a plethora of research and literature investigating the methods used to bring Germany out of their economic crisis. Generally, scholars often identify ordoliberalism as the economic policy utilized by the German government to overcome the economic

catastrophe. The framework of ordoliberalism was developed prior to World War II. In the 1930s, a few professors from the University of Freiburg in Germany developed a robust and conducive economic/legal framework that could curtail monopolistic encroachments, respond to economic burdens, and maintain a certain degree of freedom for the populous. The professors often credited for the early development are the economist Walter Eucken and two legal scholars Franz Böhm and Hans Grossmann-Doerth. Over time ordoliberalism began to solidify and was identifiable by its distinct characteristics. But what exactly is ordoliberalism? Well, like everything, it depends who you ask.

In general, ordoliberal principals can be summarized as a state centric approach that provides a viable economic framework which supports the state’s social and economic interests. In terms of monetary policy, stability is key for ordoliberalism. Fiscal stimulus measures should be avoided if they make the overall economy unstable. The direct inverse of French and U.S. fiscal policies which don’t want to necessarily intervene fiscally but if things are dire the state will apply fiscal stimuli to help the economy.

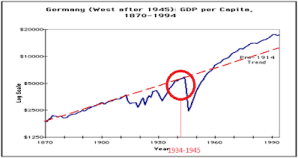

Germany is opposed to such measures, mainly due to the hyperinflation experienced during the 1930’s. These measures had extreme effects on society and arguably contributed to the rise of the Nazi party. Ironically, the Nazi party recognized that hyperinflation may indeed lead to societal instability and began to develop the early foundations of ordoliberalism. The post Nazi German government also utilized and implemented ordoliberal policies after World War II. However, a lot of Germany’s development can be credited to generous aide offered by the USA, with little to no strings attached. Results came fast for the German economy. Between the 1950s-60 the German GDP rose roughly 8 percent every year. In comparison to other nations in the region, Germany’s growth was faster than any other nation within continental Europe. Germany’s rapid economic growth subsequently gave rise to higher living standards within that ten-year span. This initial exponential growth would set up a new powerhouse in Europe in terms of economics. And further, ordoliberalism was then acknowledged as a viable and legitimate economic alternative to the neoliberal economic framework touted by England and the US. Instead of increased debt, nations could monitor their spending and limit government fiscal intervention to achieve economic growth.

But recently ordoliberalism has come under scrutiny. This piece will attempt to answer whether German ordoliberal policies have hindered modern economic progress for the European Union. The world economy has radically transformed since the 20th century when Germany “manifested” its economic miracle via ordoliberalism. And the argument put forth will be that ordoliberal policy is slow in recognizing an economic crisis, impacting societies ability to respond in a rapid and prudent manner. Further, when an economic crisis is finally identified, the ordoliberal policies set forth are often counterproductive in terms of successfully overcoming the crisis. In contrast, a better approach would be one which attempts to address economic crisis within the context of the crisis itself. We will call that approach “economic pragmatism”.

First, we will commence by providing a bit of a literature review on the topics at hand. After the literature review section is finished we will go on to discuss the framework I’ll be relying on. Namely, the framework will be of a pragmatist nature in terms of economics. Then a case study on Germany’s response to the Eurozone crisis will be discussed. Analyzing the Greek economic crisis will enable us to analyze the implementation of ordoliberalism to a specific modern crisis. Thereafter, a comparison between other economic policies and ordoliberalism will give us insight on where ordoliberalism gets things wrong.

Ordoliberalism as economic/legal policy has its origins in Germany. Viktor Vanberg has highlighted the development of ordoliberal thought and how the ideology has been perverted from its intellectual origins. The founders of Ordoliberalism actually fully understood that the ideology wasn’t perfect, and Vanberg notes that the idea of the strong state has been grossly misinterpreted. The “strong state” phrase that comes out of ordoliberalism was originally understood as a state that is constrained by a political constitution which prevents government from becoming the target of a special interest. For example, no single interest, such as the oil industry, should have undue influence in government affairs. Nowadays the “strong state” notion is interpreted more simply. Now people understand that the strong state only creates the economic and legal dimensions of a certain nation and the state should not interfere the economy. But the nation is limited fiscally since it is not allowed to stimulate the economy “artificially” via stimulus provisions. Research conducted by Sebastian Dullien and Ulrike Guérot suggests that the ordoliberal ideology has become the de facto rule of European Union policy in terms political and economic measures. This means that ordoliberalism has become the dominant ideology in the European Union. Though there are critiques of the ideology within the EU, Dullien and Guérot note that ordoliberalism has become “mainstream” in the EU. So that means voices of critique are marginalized in the sphere of the European Union since leading government officials commonly refer to ordoliberal principals as the “right” and only “true” ways to conduct economic policies . The de facto nature of ordoliberalism in the EU sphere can be connected to research done by Matthias Matthijs. He explains that Germany’s economic policies seem to adhere to an “ideas over interests” policy. Put simply Germany often undercuts economic stability and growth in favor of maintaining and adhering to the strict tenants of ordoliberalism. And quite often nations aren’t too keen to push back since the ideology is seen as the consensus and not only that but it is seen as the “absolute” economic truth. The domineering nature of ordoliberal thought in the EU allows readers to infer that perhaps Germany is more worried about reinforcing it’s ordoliberal rules instead of trying to ascertain the best measures to mitigate an economic crisis . That inference brings us to the theoretical framework of the paper, which will take an economic pragmatist approach to economic crises.

Pragmatism: A Better Approach?

The person often credited with innovating the pragmatic economic approach is Grzegorz Witold Kolodko. He laid out this framework in his book called Truth, Errors, and Lies: Politics and Economics in a Volatile World . The pragmatic approach will allow us to critique the current policies used by the EU. New economic pragmatism can be defined as an economic approach that attempts to solve economic crisis within the context of the crisis itself. It doesn’t rely on any specific ideology per se, but rather it attempts to compromise between economic policies at the national, international or regional economic levels. Though national, regional, and international entities may have agendas which are juxtaposed, there still exists a possibility for agreement. By mixing various elements of the juxtaposed economic policies a general consensus can be established. But what sets economic pragmatism apart is that it focuses to address three fundamental economic questions.

What’s the best route to economically sustainable growth?

What’s the best approach to insure social stability?

What’s the best approach in respects to the environmental sustainability?

Furthermore, it assumes that the recent trend of the globalized economy is irreversible and this factor must be taken into account when attempting to solve economic issues. Economic pragmatism neither endorses or disavows globalization, but quite simply globalization is categorized as a constant, a phenomena that must be accounted for when dealing with 21st century economic issues. This assumption doesn’t give way for extreme paradigm shifts. So, given that assumption, no overt disassembling of globalization will be considered within this piece. No matter how tempting revolution may be. In terms of analyzing Germany’s ordoliberal policies during the Eurozone Crisis, new pragmatic methods will be used to analyze Germany and Europe’s mistakes within the crisis. It will highlight some assumptions that were made during the crisis, and in turn discuss how and why they aren’t necessarily true via comparison to other crises. Since Germany largely relies on ordoliberalism to implement economic and political policies, the framework will display the folly of such measures. Quite simply there’s no single economic ideology that can be relied on to address any economic crisis. Strict adherents to ideological principals may in fact do more harm than good in terms of solving a crisis. But it’d be remiss to not acknowledge why such behavior exists. After all, if ordoliberalism has worked before , assuming it will work again isn’t illogical. Human’s in general are keen to use methods that they are familiar with, especially if they have worked before. But being an absolutist in terms of ideology when policies aren’t working is a cause for concern. It’s this lack of flexibility that can hamper economic development, sustainability, and innovation. The idea of inflexibility will be discussed further in the analysis of Germany’s Eurozone response. And it will be accompanied by a pragmatic study specific to the Greek crisis to describe some alternatives to the current approach taken by the Eurozone. Now that we have an understanding of economic pragmatism is coming to a close, lets shift out focus to Germany’s response to the Greek eurozone crisis.

Ordoliberalism In The Greek Economic Crisis

In order to offer a critique of Germany’s ordoliberal implementation in times of crises we must analyze the specific measures taken within a given economic crisis. The most comprehensive and recent information can be found when we investigate the German political order’s response to the Eurozone Crisis. When analyzing this response, we can find two key problem areas that have contributed to the economic downturn of certain nations, namely Greece. Firstly, German ordoliberal policy seems to vehemently deny the potential for an economic crisis, even though it’s apparent that an economic downturn will likely happen. And lastly, a strict adherence to policies that encourage austerity despite the fact that the reality of suggests that these measures are counter intuitive. These factors will be analyzed under the context of the Eurozone crisis of 2008. We will also see how these measures go against the plans of economic pragmatism which encourage economically sustainable growth, civic stability, and environmental sustainability. Now let’s transition to how Germany’s ordoliberal hegemony was slow to act to the Greek crisis.

Delay

In light of the world financial crisis of 2008, governments were quick to act to curtail the damaging effects of the crisis. In terms of short-term responses, The Federal Reserve, Bank of England, and European Central Bank all introduced measures that increased liquidity. The Federal Reserve resorted to quantitative easing which allowed banks to purchase US government debt, essentially creating bailouts for entities that were “too big” to fail. But these measures didn’t necessarily help in the long term for the European Union. Specifically, certain nations were in desperate need of bailout assistance, but those demands were largely ignored.

By dismissing and denying claims of bailout assistance, Germany’s political guard was able to make sure it was in a position to elevate the effects of the Great Recession when it came to German economic interests. Helen Thompson notes that Angela Merkel a few years into the Great Recession remarked “I don’t believe that Greece has any acute financial needs from the European community and that’s what the Greek prime minister keeps telling me” . Despite Merkel’s beliefs and the rhetoric of the Greek Prime minister, data suggests Greece absolutely needed financial assistance. Prior to these remarks roughly 100,000 Greek companies went bankrupt, and unemployment was accelerating at a rapid rate But due to Germany’s political and economic dominance in the Eurozone, Merkel’s sentiment meant that Greece’s crisis wouldn’t get any immediate active intervention to prevent a deeper crisis. Merkel’s regime continued to delay a Greek Bailout but eventual in May 2010 a bailout was absolutely necessary to avoid an economic catastrophe in the Eurozone. But aide would only be given if Greece accepted austerity measures. But such a delay hindered Greece’s potential for economic recovery, in an economic crisis time is literally money. Delaying a response to a crisis can be the difference from a comprehensive recovery and spiraling further into an economic disaster. Greece needed a quicker response. The response should have come much earlier, not ignored until the brink of a Eurozone disaster was evident. Research done by Christina D. Romer and David H. Romer has suggested that quick responses in the face of economic “shocks” are important. They write:

“In nearly every postwar recession, policymakers have been quick to discern the onset of recession and have responded to the downturn with rapid and significant reductions in nominal and real interest rates. Plausible estimates of the size and speed of the effects of these interest rate cuts suggest that they were crucial to the subsequent recoveries”

In terms of economic pragmatism, identifying the issue early would be of outmost importance. That’s because the Romers’ research suggests that economic sustainability is directly impacted by the rapidity of the responsiveness. But Germany’s delay comes from an interest to uphold the tenants of ordoliberalism. Matthjs suggests that the current German political order would much rather hold on to and uphold the dominance of their ordoliberal principals than actually attempt to solve the crisis explaining that:

“Since the German government of Christian Democrats and Free Market Liberals had quickly framed the crisis as a twin crisis of fiscal profligacy and lack of competitiveness in the southern periphery, fiscal policy would revert back to the original and rules-based consensus at Maastricht, but with substantially stronger guarantees of actual implementation of those rules”

Unfortunately, this trend of delay seems to be continuing into 2019. The German political order has refused to acknowledge the need for an economic stimulus in the face of slowing economy in 2019. Foreign demand for German exports has begun to shrink, bringing the country’s economy to a standstill. But yet the German government has done little to nothing to implement any measures that may countervail the economic contraction. Furthermore, in the midst of the Covid-19 pandemic ordoliberal nations, such as the Netherlands and Germany, have exhibited resentment for paying for southern Europes stimulus since it would be punishing the “savers”. Odd considering the dire circumstances. However, ECB president Christine Lagarde has emphasized the need for solidarity and fiscal stimuli to help mitigate the losses during the outbreak. This strict attachment to austerity may in fact be counter intuitive in terms of economic recovery and sustainability. The reasons why will be explained in the following section.

Austerity

As time has gone on it has become clear that ordoliberal measures imposed on Greece have done more harm than good for the Greek economy, people, and politics. Arguably, the specific measure that has done the most observable harm is the policy of austerity. In basic terms, austerity refers to government policies that aim to reduce public sector debt and overall government spending. Though some reduction in government spending can offer marginal assistance; extreme cuts and repayment stipulations can be detrimental to an economy. This proposition has been evident throughout history. Ironically, Germany was one of the nations that was negatively affected by austerity measures. After World War I, the “victors” of the war imposed harsh repayment plans on the Germans. These measures were austere and subsequently lead to the Nazi’s coming into power. Furthermore, Joseph Stiglitz (a Nobel Prize wining economist) notes that the phenomena of austerity doesn’t necessarily result in economic recovery. He notes:

“Austerity had failed repeatedly, from its early use under US President Herbert Hoover, which turned the stock-market crash into the Great Depression, to the IMF “programs” imposed on East Asia and Latin America in recent decades”

Stiglitz goes on to describe how things haven’t really changed in terms of modern day austerity implementation. Greece is currently suffering, and not reaping much economic benefit. The data seems to correspond to Stiglitz’s inference. In Greece, unemployment fluctuates between 20-25%, and for young adults it’s at about 50%. These figures have been detrimental to the Greek economy. Further, through 2009- 2019, the Greek GDP has fallen from roughly 90% to 60%, the consumption per capita has fallen from about 100% to 76 %, and all of these factors mean that the standard of living has fallen as well. This loss is largely attributable to the austerity measures the Greeks were coerced into by the EU. In order to receive recovery aid, a considerable cut in government spending was necessary for the Greeks. A classic quid pro quo agreement. One of the specific austerity measures that was implemented was that Greece was required to restructure its pension system to aid in cutting government spending. Pension payments had absorbed 17.5 percent of GDP, higher than in any other EU country . Austerity measures required Greece to cut pensions drastically. Higher pension contribution by workers was another perquisite along with limited early retirement in order to keep pension repayment low. Limiting government spending is often a good idea for economies but only in the correct conditions. The Greek economy wasn’t built for such a radical shift, pensions were a fundamental part of the overall Greek economy. Half of Greek households relied on pension income since one out of five Greeks were over 65 years old. We can assume that workers weren’t thrilled about paying higher contributions, and further a huge cut in retirement pensions must have aggravated retirees. Work was also drying up, so if no one was working that meant no one was contributing to pension funds. Greece was staring a looming economic depression in the face. Greek public moral took a deep dive.

People went to the streets to express their discontent. Civil disorder would become the norm in Greece.

Civil Unrest

Not only did the economy suffer from the ordoliberal austerity measures but civil society would be affected as well. From 2010 to 2012 a series of massive public anti-austerity movements began to demonstrate in towns across Greece. An article by Angelique Chrisafis , written in the midst of one of the Anti-Austerity demonstrations in 2011, describes the situation as thus:

Doctors and nurses recently staged walkouts over hospital cuts. Taxi drivers have hobbled Greece with strikes in the past two weeks, protesting at government plans to open up the industry. Their tactics included blocking ports and opening the Acropolis ticket office to let tourists in free….Greece’s long-running “civil disobedience” movement, where ordinary citizens refuse to pay for anything from road tolls and bus tickets…has not fizzled out in the summer holidays. The “We Won’t Pay” offensive is championed as the purest form of “people’s power”

Chrisafis’s article articulates the social moral of the Greek people during these austerity measures. The people had lost hope in their government, and responded by not complying to societal norms. Some of the demonstrations were more violent in nature, and vandalism also occurred. When a society is actively participating in acts of civil disobedience which attempt to the undermine the political/economic order then there may be economic consequences that result. The explanation for that is that when people are protesting economic policies, refusing to pay for services, and not getting paid their wages that means that the economy isn’t running at maximum efficiency. Not only that but society itself isn’t functioning the way it normally does. But not only did the austerity measures have an effect on the economy and society but it also had repercussions to the biological environment.

Environmental Consideration

The biological environment in Greece was also negatively affected by the economic crisis. Due to the aforementioned low wages caused by the crisis, Greeks were forced to look for cheap products in their daily life. Martha Nanou explains that this behavior had a negative effect on the environment. In her study focusing on the effects the financial crisis had on the overall air quality she explains:

“[I]ncreased heating fuel taxes that were used in order to support Greek economy, obliged people to find alternative, cheaper solutions that caused even more air pollution in large cities. More specifically, in Thessaloniki, the second largest city in Greece, the increased price of fuel oil led the citizens of the city to use the cheapest wood during winter. This increase of cheap wood products use for domestic heating, resulted in an increase of the levels of cesium (Cs) (Stoulos et al., 2014). For these reasons, Thessaloniki was characterized as one of the most air polluted cities within Europe during the past two years”

Changing to the wood alternatives may have had a negative effect on the air quality. But, if one takes a step back to analyze the situation, this also means that trees were being cut down at a much higher rate than before. Greek environmental authorities noted that illegal tree cutting had become the norm. And that the environmental ministry has issued over 3,000 lawsuits and seized over 13,000 tons of illegally chopped down trees.. This behavior outlines the underlying effects ordoliberal austerity measures can have on a nations that are not ready to cope.

Different Models

One of the way’s this situation could’ve been avoided is that the Greek crisis should have been addressed much sooner. But even if the crisis was caught a bit late, there could have been other measures that may have lessened the probability of a catastrophic economic crisis, societal upheaval, and environmental degradation. Namely measures which weren’t austere in nature.

Economic pragmatism would have attempted to look at a holistic solution instead of responding to the crisis via a specific economic theory. This approach would ensure that the economy wouldn’t suffer too much, society wouldn’t fall into years of civil unrest, and perhaps the environment wouldn’t be as negatively affected. Austerity wasn’t the only method available to handle the Greek Eurozone crisis. It was just the most convenient. Economic research suggests that debt restructuring doesn’t need to necessarily be strict in nature to overcome a sovereign debt crisis. Andreas Muller, Kjetil Storesletten, and Fabriziso Zillibotti are researchers who suggest austerity isn’t the only way. They provide an in depth analysis on debt restoration and reform relying on four “building blocks” , writing:

“[D]ynamic theory of sovereign debt that rests on four building blocks. The first is that sovereign debt is subject to limited enforcement, and that countries can renege on their obligations subject to real costs ….The second building block is that whenever creditors face a credible default threat, they can make a renegotiation offer to the indebted country. This approach conforms with the empirical observations that unordered defaults are rare events, and that there is great heterogeneity in the terms at which debt is renegotiated, as documented by Tomz and Wright (2007) and Sturzenegger and Zettelmeyer (2008). The third building block is the possibility for the government of the indebted country to make structural policy reforms that speed up recovery from an existing recession.1 The fourth building block is that reform effort is not contractible nor can markets commit to punish the past bad behavior of sovereign governments.”

They go on to argue that all of these measures would have an overall positive effect to a nation that’s in sovereign debt. Equilibrium isn’t achieved when austerity is implemented, but when nations are allowed to have more of a say in debt renegotiation and aren’t punished for the economic crisis then an economy can smoothly recover. This is important lesson for future economic crisis since strict adherence to economic theories may not enable a proper recovery for an economy.

Another alternative can be found by observing the US. The US avoids regional recessions by distributing risk across the states. Programs such as Social Security or unemployment insurance help support the poorer regions, and fundamentally make sure that pooer states don’t implode when they fall into recession. This idea has been propagated by several EU leaders, but due to the political clout of the Frugal Four their propositions fall through. For example, former Prime French Prime Minister Francois Hollande, has suggested that Europe move in this direction, with wealthier states funding a bigger European Investment Bank that can bankroll industrial projects in poorer countries.

Lastly, another model that can be emulated is the economic miracle which occurred in Singapore. A century ago, Singapore was an island with little to no economic clout. But after a series of pragmatic economic policies Singapore was transformed into a major manufacturing and financial center. They mixed low taxes, few capital restrictions and liberal immigration policies with policies that are often considered to be socialist such as heavy government spending on social services like housing, banking and health care. (Read more here)

In all we can see how German ordoliberlist policy may in fact make a crisis worse. However, understanding the gravity of the crisis early and responding in a manner which actively attempts to help can lessen the negative effects of a crisis. Some of those effects being economic, social, environmental. Strict adherence to austerity isn’t a necessary response to a crisis. The political dimension of this paper can be said to be of a pluralist nature. Pluralist because it doesn’t restrict itself to one economic theory but rather allows for a more flexible economic approach. But in terms of economics it takes a pragmatic approach since it attempts to take into consideration elements which attempt to solve an economic crisis by not being restricted in terms of ideology.

Sources:

“Austerity – Overview, Examples of Austerity Policies, and Advantages.” Corporate Finance Institute, corporatefinanceinstitute.com/resources/knowledge/economics/austerity/.

Bernake, Ben s. “Financial Markets, the Economic Outlook, and Monetary Policy.” Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, http://www.federalreserve.gov/newsevents/speech/bernanke20080110a.htm.

Burgmann, Verity. “Conclusion.” Globalization and Labour in the Twenty-First Century, 2016, pp. 237–242., doi:10.4324/9781315624044-11.

Chrisafis, Angelique. “Greece Debt Crisis: The ‘We Won’t Pay’ Anti-Austerity Revolt.” The Guardian, Guardian News and Media, 31 July 2011, http://www.theguardian.com/world/2011/jul/31/greece-debt-crisis-anti-austerity.

Dullien, Sebastian, and Ulrike Guérot. “The Long Shadow of Ordoliberalism: Germany’s Approach to the Euro Crisis.” European Council of Foreign Affairs, 2012, doi:https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/8da0/9ef76b1598eadd96966c9757054bfc3652f5.pdf2.

Eichengreen, Barry, and Albrecht Ritschl. “Understanding West German Economic Growth in the 1950s.” Cliometrica, vol. 3, no. 3, 2009, pp. 191–219., doi:10.1007/s11698-008-0035-7.

EUROSTAT. “First Estimates for 2018 – Wide Variation of Consumption per Capita across EU Member States – GDP per Capita Ranged from 50% to 254% of EU Average.” European Commission – PRESS RELEASES – Press Release – First Estimates for 2018 – Wide Variation of Consumption per Capita across EU Member States – GDP per Capita Ranged from 50% to 254% of EU Average, europa.eu/rapid/press-release_STAT-19-3245_en.htm.

Galofré-Vilà, Gregori, et al. “Austerity and the Rise of the Nazi Party.” 2017, doi:10.3386/w24106.

James, William. “Pragmatism: A New Name for Some Old Ways of Thinking.” 1996, doi:10.1037/10851-000.

Kolodko, Grzegorz. “The New Pragmatism, or Economics and Policy for the Future.” Acta Oeconomica, vol. 64, no. 2, 2014, pp. 139–160., doi:10.1556/aoecon.64.2014.2.1.

Kołodko, Grzegorz W. Truth, Errors, and Lies: Politics and Economics in a Volatile World. Columbia University Press, 2011.

Matthijs, Matthias. “Powerful Rules Governing the Euro: the Perverse Logic of German Ideas.” Journal of European Public Policy, vol. 23, no. 3, 2015, pp. 375–391., doi:10.1080/13501763.2015.1115535.

Muller, Andreas, et al. 11 Sept. 2016, http://www.brown.edu/academics/economics/sites/brown.edu.academics.economics/files/uploads/Fabrizio%20Zilibotti_Macro%20Seminar%20Paper_0.pdf.

Nanou, Martha. “Greek Financial Crisis and Environment. Can Crisis Be an Opportunity?” Http://Edepot.wur.nl/357781, May 2015.

Romer, Christina, and David Romer. “What Ends Recessions?” 1994, doi:10.3386/w4765.

Sindreu, Jon. “Don’t Expect a Meaningful Fiscal Push From Germany.” The Wall Street Journal, Dow Jones & Company, 20 Aug. 2019, http://www.wsj.com/articles/dont-expect-a-meaningful-fiscal-push-from-germany-11566306054.

Stiglitz, Joseph E. “A Greek Morality Tale: Why We Need a Global Debt Restructuring Framework.” The Guardian, Guardian News and Media, 4 Feb. 2015, http://www.theguardian.com/business/2015/feb/04/a-greek-morality-tale-global-debt-restructuring-framework.

Thompson, Helen. “Germany and the Euro-Zone Crisis: The European Reformation of the German Banking Crisis and the Future of the Euro.” New Political Economy, vol. 20, no. 6, 2015, pp. 851–870., doi:10.1080/13563467.2015.1041476.

Tilford, Simon. “Germany Is an Economic Masochist.” Foreign Policy, 21 Aug. 2019, foreignpolicy.com/2019/08/21/germany-is-an-economic-masochist-recession-merkel/.

Tinios, Platon. Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung, vol. 04, 2016.

Vanberg, Viktor J. “The Freiburg School: Walter Eucken and Ordoliberalism.” Econstor, 11 Apr. 2004.